Written By: Al Marie Campana

October 29, 2021

Writing is the result of a miracle. Composing a text requires whole-brain engagement. For one, the frontal lobe manages sorting through ideas for a topic, choosing one, and making an organized plan of idea presentation. Next, the hippocampus helps to create or recall knowledge from long-term memories. Finally, these memories must be translated into words that retell the ideas the hippocampus brought up - words that eventually will have to be transcribed.

Broca's Area accomplishes this task of translating knowledge into words found in the left hemisphere of the frontal lobe in conjunction with the Wernicke's Area, which is located in the left temporal lobe. The Wernicke's Area is taxed with the role of understanding, while the Broca's Area oversees the production of new language. If understanding is not achieved, the Broca's Area becomes responsible for producing new ideas that the Wernicke's Area will have to sort for understanding yet again.

As these processes are taking place, researchers have found, through brain scans, that both the visual cortex and the Broca's Area light up when an experienced writer is composing text. Activation in the visual cortex, found in the brain's occipital lobe, suggests the writer uses inner narration to see the story they are telling with their minds' eye. The motor area found in the back of the frontal lobe signals the muscles of the hand to either type the correct keys in the proper order or to hold a pencil/pen to form physical letters on paper to encode the ideas.

These processes eventually become automatic because of the Caudate Nucleus, which is found deep within the brain. Essentially, the Caudate Nucleus coordinates all the processes working together to become more efficient when repeated practice occurs. Efficiency only stems from this repeated practice. I guess practice doesn't make perfect; instead, it breeds efficiency.

It is no wonder, then, that only about 27% of U.S. students between the grades of four and twelve are proficient in writing, according to the NAEP (2020; https://www.nationsreportcard.gov) National Report card. This number further diminishes to 25% when we filter that data further to focus our attention on how our public-school students perform without their private school counterparts. Let that sink in. Only twenty-five percent of our students can write proficiently. The low writing proficiency score indicates that 75% of our students cannot communicate their ideas proficiently in written form. Truth be told, many administrators, teachers, and parents have no idea how to tackle this problem.

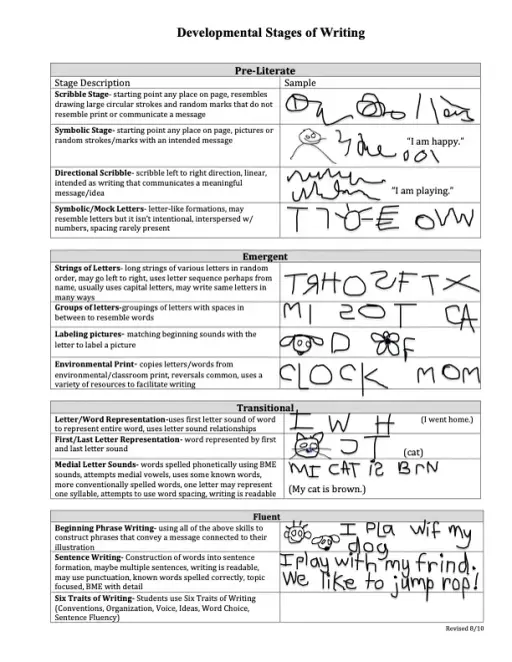

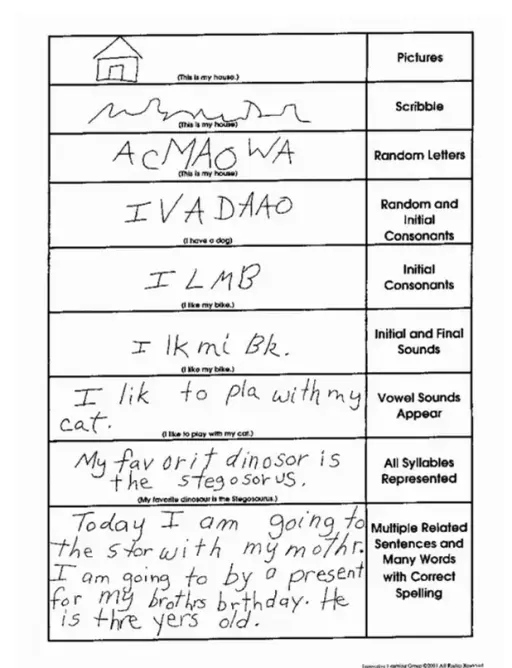

Developmental Stages of Writing

The first step toward being able to remediate the problem at hand is to consider the developmental stages of writing. Understanding what children should be able to do at each given stage and how their writing ought to look will be helpful to assess the exact need of each child.

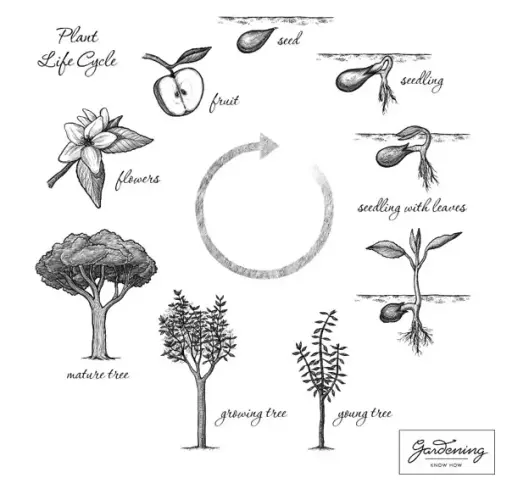

The Lifecycle of Writing

One effective comparison is to consider the developmental journey required to compose a piece of writing as similar to the development of a flowering tree.

1. The Seed Stage

During the seed stage, the writer becomes aware of all the sounds that surround them. These sounds eventually gather meaning when they are put together to create words. Finally, these words come together to make sentences that enable communication between two individuals. It is important to note, though, that language is first developed orally. During the seed stage, the correspondence of letters and sounds (phonics) is not yet introduced. Without a solid foundation in phonological awareness, we are left with seeds not ready to sprout their leaves.

2. The Seed with Leaves Stage

The seed begins to germinate, and the correspondence of sounds to symbols begins to unfold. Young writers are exposed to written text, and they start to understand that each symbol on a page corresponds to specific sounds. During this stage, the young writer begins their journey into understanding phonics and explores the realm of forming letters. Their small hands attempt to grip a pencil, crayon, or marker, and they attempt to spell the words they hear at times using inventive spelling. Thus, like a leaf stemming from a seed, phonics begins to grow and develop in the young author’s mind.

3. The Seedling Stage

Inventive spelling begins to disappear as novice writers begin to understand the letter-sound correspondence. They begin to understand the six syllable types, so they begin to correct a lot of the inventive spelling.

4. The Sapling Stage

As a result of joining syllables together, inexperienced writers begin to develop further their ability to construct well-developed words. At this point, the writer begins their attempt to formulate sentences formed by putting together words.

5. Small Tree

With practice, young writers begin to combine sentences to produce paragraphs. During this stage, inexperienced writers have difficulty keeping ideas in order and on topic. Therefore, like most small trees, we must ensure to monitor its growth consistently and provide all of the necessary “nutrients” (mentor text, positive and constructive feedback, consistent guidance) needed to ensure the writer can fully develop into a confident writer. This stage is where the six traits of writing should be monitored and polished.

6. Growing Tree

The growing tree stage is marked by a young author who becomes more comfortable putting sentences together to create cohesive paragraphs. They begin to combine paragraphs to form different types of text. During this stage, young writers should be encouraged to pay attention to the audience, purpose, format, and topic of their writing. Students should be taught how to revise and edit their work.

7. Mature Flowering Tree

With lots of practice, the students during this stage are ready to tackle any type of writing. They will be able to implement all of the six traits and fluently work their way through the writing process.

Just like a tree, young writers will forever be changing. Whether a storm beats its wind against its branches or a pest begins to eat of its trunk, a tree is consistently adapting to thrive over the elements. Similarly, young writers will have to learn to face many adversities in their writing journey.

Handwriting: Focus on What Matters

- Grip: Proper grip is essential for proper development. Explicitly teach and monitor your student’s grip.

- Directionality: Each letter is formed with a specific sequence that must be followed. To avoid a cognitive overload, explicitly teach the correct direction students should take when completing a letter.

- Placement: Letters, words, and sentences should not be floating. Always encourage your student to touch the base line when writing their letters and numbers.

- Spacing: Spacing between letters in a word and spacing in between words should be monitored closely.

- Start: Make sure to explicitly teach young authors the exact starting point of each letter. When students start their letters on the base line, correct them immediately.

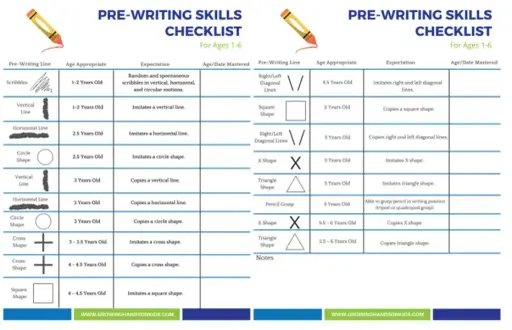

This chart shows the basic shapes children should know by each age.

Writing Structure: The Architecture of Written Expression

Sentence Parts: Teach students about the parts of a sentence and the correct way to manipulate its different parts to create different sentence types.

- Capital Letter

- Subject

- Verb

- Makes Sense

- End Mark

Sentence Types:

- Simple

- Compound

- Complex

- Compound-Complex

Paragraph Parts: Every sentence within one paragraph should speak about one main topic. All ideas presented should be organized in a way that makes sense to the reader.

- Topic Sentence

- Supporting Details

- Elaboration Sentences

- Transitional Sentence

Text Structure: The text structure will determine the language that should be included in the text. Empower your student by providing the correct vocabulary to convey the right message.

- Description

- Sequence

- Compare and Contrast

- Cause and Effect

- Problem and Solution

Text Type: The organization of words in a page, the placement of different text elements, and the number of paragraphs needed to complete a text depend on the text type.

- Essay

- Letter

- Procedure

- Discussion

- Report

- Response

- Recount

- Explanation

The Writing Process: A Roadmap to Success

- Effective Planning: Students will not have a natural initiative to plan their writing before they attempt to address a writing prompt. It is imperative that students understand the importance of planning efficiently to avoid writer’s block and a disorganized piece of writing.

- Revision Strategies: After students spend time writing, revision is a must. Teaching our students to use tools like highlighters and editing marks will encourage them to consider revising their papers. Modeling the correct way to revise and providing a checklist to consider during the revision will empower the young author to revisit their writing.

- Six Traits of Writing +1: Most teachers and students tend to focus on the conventions of writing; in doing so, we have slowly killed the voice of our writers. The six traits of writing become the filter through which students can assess their writing and the tool that will enable them to take their writing to the next level.

- Presentation

- Ideas

- Conventions

- Voice

- Organization

- Word Choice

- Sentence Fluency

Important Considerations

Everyone can indeed learn, but it is equally important to remember that not everyone learns in the same manner. For example, let’s consider the ELL (English Language Learners) population.

- Letter-Sound Correspondence: The Spanish language only has one vowel sound per vowel, and that the letter “w” does not share the sound the “w” makes in the English language.

- Sentence Structure: The English sentence structure is not universal. For example, adjectives in English are placed before the noun. In Spanish, the noun comes first, and then the adjective is placed. Also, in English, the object follows the verb, while the verb precedes the object in Korean.

Taking the time to consider these differences is of utmost importance when approaching the task of teaching writing. If our young authors cannot hear the same sounds that we are trying to share with them, it will reflect in their writing. The only way to correct this is to approach it with explicit instruction.

Now What?

Clearly, the writing process is one filled with many hills and valleys. Some students cruise right through all the developmental stages without any problems. In contrast, others grapple with the rules, tasks, and ideas to find themselves lost in a forest of frustration and defeat. So how do we nurture these developing authors? We assess, monitor, and intervene immediately.

Keep track of each child’s strengths and weaknesses and encourage them to persevere. Do not be afraid to explain the complexity of the writing task and what is happening in the brain when they attempt to write something.

Explaining writing complexity may relieve them from the belief that there is something wrong with them and will normalize the difficulty they may be experiencing with the task at hand.

As you approach your next writing activities with students, remember all that is involved in this process, pray lots for wisdom and guidance, and make it safe for students to fail!

Al Marie Campana, NILD PCET