Effects of NILD Educational Therapy for Students with Learning Difficulties

Educational Therapy Strategies

Assessment

Written By: Dr. Kathy Keafer

This research project was undertaken in partial fulfillment of a Doctor of Education degree at Regent University in Virginia Beach. Only limited information from the study is presented in this article. To access the complete study, including a full literature review, complete presentations of group demographics and statistical procedures as well as findings regarding written expression, please contact NILD.

The National Institute for Learning Development (NILD) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to training educators to work with children and adults with learning difficulties through an individualized program of educational therapy. NILD defines educational therapy as an intervention that first determines a student’s patterns of learning strengths and weaknesses and then provides intense instruction in a one‐to‐one setting to remediate the identified educational weaknesses. NILD Educational Therapy® focuses primarily on basic academic skills such as reading, spelling, written expression, and mathematics. Improved skills are developed to achieve grade‐level academic proficiency using a combination of direct instruction (Carnine, Silbert, & Kameenui, 1997) and mediated‐ learning strategies (Feuerstein, 1980). NILD educational therapists are professionals who create a supportive learning environment and offer an intensive intervention to students with learning challenges based on the appraisal of information received from parents, classroom teachers, and psychoeducational evaluations.

NILD Educational Therapy is intended for students in grades 2‐12 and is adapted to appropriate instructional levels for each student. The program includes 24 different techniques from which the educational therapist chooses specific techniques that will most appropriately meet the academic and cognitive processing needs of individual students. A typical NILD Educational Therapy session usually includes 8‐12 techniques. Several core techniques that encourage strategy development, self‐questioning, and oral language proficiency within the framework of learning basic skills in primary academics have been found to be the most useful (Hopkins, 1996). The core techniques include Blue Book, Dictation and Copy, Buzzer, Math Block, and Rhythmic Writing. Most NILD Educational Therapy sessions routinely include these five core techniques.

Although the use of NILD Educational Therapy has grown substantially since its inception more than 25 years ago, the organization has not yet established program efficacy. Neither of the studies previously completed (Benson & Scott, 2005; Hopkins, 1996) gained professional recognition, which has created a problem for NILD. Because these studies, as well as accumulated anecdotal evidence, appear to suggest efficacy for the NILD program, the organization would like to continue to move beyond private schools and offer programs in public school and community‐based settings. The current educational environment, however, increasingly demands validated, empirical research. Not having an empirical research base has made it difficult to find entrance into the public arena, suggesting the necessity for the NILD program to have a comprehensive, well‐designed study that attempts to establish the efficacy of the intervention.

The NILD program has traditionally focused on students with a specific learning disability (SLD) who were usually identified with an ability‐achievement discrepancy. Because the program has been located principally in private schools, the SLD population identified often displayed average to above average ability but rarely exhibited significantly below average achievement because many of the schools exclude such students. Public schools, however, rarely identify a student as SLD unless they are presenting below average achievement. Consequently, it was necessary for this study to be directed at establishing the efficacy of the NILD program for students who meet the more typically accepted characteristics of SLD that often includes both an ability‐achievement discrepancy and below average achievement.

Given the limitations of previous research, four areas emerged as focal points for the current effort: (a) overall effectiveness of the NILD program for students demonstrating below average academic achievement, (b) effectiveness for students whose profiles are discrepant compared with those who are not discrepant, (c) effectiveness with younger versus older students, and (d) which specific skills are most impacted. From these concerns four research questions were developed. Each question only considered the skills of reading (decoding, fluency, and comprehension) and written language (spelling and sentence writing) because most students with SLD demonstrate significant problems in these areas. The four research questions follow:

- Does NILD Educational Therapy help students who are below average in reading and written language achievement improve their reading and written language skills?

- How do students enrolled in NILD Educational Therapy with ability‐achievement discrepancies [underachievers ( UA)] whose achievement is below average in reading and written language skills differ in improvement of reading and written language skills from students whose achievement is also below average but who do not display ability‐ achievement discrepancies [low‐achievers ( LA)]?

- Do students enrolled in elementary grades whose achievement is below average in reading and written language skills respond to NILD Educational Therapy differently from students enrolled in middle school whose achievement is also below average in reading and written language skills?

- On which specific reading and written language skills as measured by five subtests on the WJ III ACH (Spelling, Writing Samples, Word Identification, Word Attack, Reading Fluency, and Passage Comprehension) do students with below‐average achievement make the most progress as a result of NILD Educational Therapy?

Only currently enrolled students with below average achievement scores were eligible for the study. Data for each student was collected at three points: (a) prior to enrollment in NILD Educational Therapy, (b) after 1 academic year or approximately 60 sessions of NILD Educational Therapy, and (c) after 2 academic years or approximately 120 sessions of NILD Educational Therapy. Information was gathered from the standard battery of the Woodcock‐Johnson III Tests of Achievement [WJ III ACH] (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001), classroom standardized testing scores, teacher checklists, and classroom grades. The scores for 172 newly enrolled students were originally received with 68 (40%) of those profiles meeting the stipulated parameters. Upon completion of the study, 39 students remained in the sample. Ninety percent of the students were Caucasian and 92% were enrolled in private schools. The sample of students obtained only allows generalization of the findings to private schools. Sixty‐nine percent of the students were male and 31% were female. Further descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Descriptive Statistics for Full Sample (n = 39) | ||

|---|---|---|

Mean | SD | |

| IQ | 96.05 | 8.18 |

| Grade Level | 5.05 | 2.52 |

| Age | 10-9 | 2.69 |

Summary of Findings

Overall, students in the study with below average achievement in reading significantly increased their skills by 8.5 standard score points (from an average of 81.6 to an average of 90.10) or 2.5 grade levels over the 120 sessions or 2 academic years of NILD Educational Therapy applied in tandem with the standard general education curriculum. Not only did the students demonstrate yearly gains as would be expected within general education alone, their progress exceeded average gains and began to close the achievement gap between them and their peers. The same students improved their skills in written expression by 7 standard score points or nearly two grade levels, representing a significant improvement that allowed them to keep pace with the average achievement of their peers. Results are graphically depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Linear effects for both reading and written language skills for full sample.

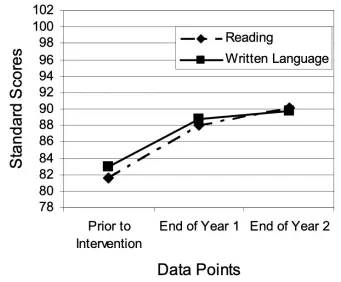

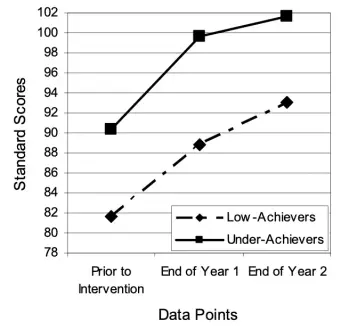

When the sample was divided into two groups (LA and UA) on the basis of the presence of an ability‐achievement discrepancy, the findings in overall reading for each group mirrored the results for the group as a whole. It may have been expected that students with a stronger ability as measured on a standard intelligence test (UA group) would have progressed at a greater rate and suggests that NILD Educational Therapy can be a successful intervention to complement the general curriculum for both underachieving and low achieving students. Results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Linear effects for reading for both achievement groups.

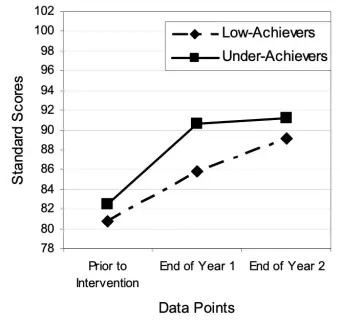

The full sample was also divided into two grade‐level groups with students beginning the program in grades 2‐5 being assigned to the elementary group and those beginning the program in grades 6‐9 assigned to the middle school group. Once again, the findings for improvement in both overall reading and written language skills for each group were not significantly different from each other and mirrored the results from the whole sample, suggesting that NILD Educational Therapy can effectively be implemented alongside the general education curriculum for the reading remediation needs of both elementary and middle school students. Results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Linear effects for reading for both grade‐level groups.

Most surprising was the trend in both reading and written expression toward substantial improvements in just 1 year of NILD Educational Therapy. Student progress in overall reading and written language skills tended to increase for the entire sample during the first year (60 sessions) but leveled off during the second year. When separately evaluating the UA and LA groups in both reading and written expression, the LA group demonstrated a more linear trend suggesting that their progress was steady over the 2 years. The UA group, on the other hand, showed remarkable progress during the first year but limited change during the second academic year.

Significant growth was also realized for each of the subskills of reading and written expression for the full sample with the NILD intervention being similarly effective for both the LA and UA groups when used alongside their general education studies. For both groups, most growth was achieved in reading comprehension, representing an important outcome since reading comprehension is considered the most important skill leading to eventual success in content reading. The positive outcome was further substantiated by an average 10.5 percentile increase in the reading comprehension subtest score over the 2‐year period for 14 of the students whose classroom standardized testing scores were available.

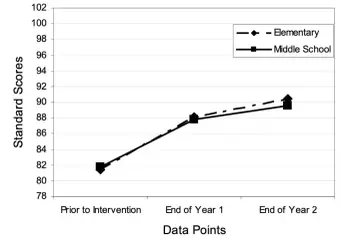

For the LA group, growth of 2.3 grade levels (11.5 standard score points) was realized over the 2‐year period and brought them from below average performance in reading comprehension to solidly in the average range. The UA group improved their reading comprehension scores by 3.5 grade levels (11.2 standard score points) over the 2 years improving from the lowest end of the average to the midlevel of the average range. Since more than 2 years of growth was experienced by each group, these students were able to begin closing the achievement gap between them and their peers. Results are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Linear effects for reading comprehension for both achievement groups.

Need for Further Research

Certainly further research is needed to definitively determine the effectiveness of NILD Educational Therapy. Follow‐up research to this study should be conducted to determine if significant progress is once again made by those students in this study who continued to a third year of intervention. Should third‐year scores in overall reading and specific skill areas reveal upward trends, the need for 3 years of educational therapy could be validated. Additionally, substantial gains would increase the likelihood that students could independently manage necessary content reading and written assignments in the future, a primary goal for all NILD Educational Therapy students.

Another follow‐up study should be completed in 2 to 3 years to determine if gains made as a result of combining 2 or 3 years of NILD Educational Therapy with a general education program were maintained or even improved. Sustained gains are the ultimate goal of any educational intervention and should be substantiated following a study such as this one. Additionally, another study that replicates the parameters of this study would further substantiate the present findings.

Most important to the future of NILD programs is the opportunity to establish effectiveness in a more widespread, controlled study that includes random sampling and greater ethnic and social diversity among participating students with deficiencies in reading and written expression. It is hoped that the present study will serve to establish NILD Educational Therapy as an intervention that holds great promise for struggling students and that the provision for a more extensive study will be realized in the near future.

References

Benson, B., & Scott, K. (2005). Data analysis to determine the effectiveness of NILD educational therapy for students with learning disabilities. Retrieved July 30, 2006, from http://www.nild.org/research.doc .

Carnine, D. W., Silbert, J., & Kameenui, E. J. (1997). Direct instruction reading (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill, an Imprint of Prentice Hall.

Feuerstein, R. (1980). Instrumental enrichment: An intervention program for cognitive modifiability. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Company.

Hopkins, K. (1996). A study of the effect of interactive language in the stimulation of cognitive functioning for students with learning disabilities. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA.

Woodcock, R. W., McGrew, K. S., & Mather, N. (2001). Woodcock‐Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing.