Written By: Lorri Wilke

May 3, 2019

Do you know any students who take hours to complete a simple assignment that might take other students only 15 or so minutes? May be those same students struggle with making decisions quickly, following multi-step instructions, or completing tasks – especially timed tasks. It seems to take them forever to tie their shoes, sharpen a pencil, or clear their desks. Maybe those same students do poorly on tests even when they know the material well. There are many possible reasons for these difficulties, and slow processing speed may be at least part of the explanation.

be those same students struggle with making decisions quickly, following multi-step instructions, or completing tasks – especially timed tasks. It seems to take them forever to tie their shoes, sharpen a pencil, or clear their desks. Maybe those same students do poorly on tests even when they know the material well. There are many possible reasons for these difficulties, and slow processing speed may be at least part of the explanation.

What is Processing Speed?

Processing speed is a rather abstract concept, and it is tricky to measure. Nonetheless, it is one of the main components of the cognitive process, and that is why it is an important skill in learning, academic performance, intellectual development, reasoning, and experience. In a nutshell, processing speed is the pace at which you take in information, make sense of it, and respond to it. In simple terms, processing speed is how fast you can get stuff done! Whether visual (letters and numbers), auditory (language), or movement, processing speed is the time between receiving and responding to a stimulus.

Processing speed is considered an executive function skill by some educators, but is it really? The term executive function has been in use for several decades, but there is great variation in how the construct has been defined. Many agree that executive functions allow us to successfully use our intelligence and problem-solving skills. Since there seems to be some confusion, I decided to go directly to a leading expert on executive function, Dr. George McCloskey, author of Essentials of Executive Functions Assessment. He told me that processing speed is not an executive function, but the two, processing speed and executive function, definitely relate.

McCloskey explained:

Processing Speed is similar to working memory, planning, reasoning, and all other cognitive constructs that we assess. In my model, I make the distinction between the cognitive construct that is being directed by executive functions…and the executive functions…that are doing the cueing and directing. Thus, in my model, processing speed, like working memory, is not an executive function, but executive functions cue and direct working memory and processing speed.

He continued by explaining why a student can do poorly on the WISC-V Coding test and then do well on the WISC-V Integrated Coding Copy.

Processing speed is there for the coding copy which is a simple processing speed task. The performance drops with the other coding test because of the increased demand for executive functions to direct the processing speed…If scores on Coding and Coding Copy are both low, the likely source of difficulty is slow PS, but it is possible that both processing speed and the executive direction of processing speed are deficient…it is possible to have good processing speed but poor executive direction of it; conversely, it is possible to have good executive control of processing speed, but that executive function awareness does not lead to a change in processing speed because there is no good processing speed available to be increased.” (personal communication, June 10, 2016)

Therein lies the connection between processing speed and executive function, and it’s an important relationship. Remember, however, processing speed is not another name for executive function, but they are definitely connected. Executive functions cue and direct processing speed, and because of this, we must target executive function skills in our therapy sessions.

Keep in mind, a student might be the smartest one in the class, but without strong executive function skills, he cannot use his intelligence well. Processing speed seems, in some ways, to drive other executive function skills.

Imagine that executive function is a car and processing speed is the engine. A fast, efficient engine allows the car to perform well and go faster. Fast, efficient processing speed allows executive functions to be performed quickly, efficiently, and appropriately. Now, just because you don’t have a Ferrari engine doesn’t mean you cannot travel from point A to point B, but the efficiency of the journey depends heavily on your processing speed/engine. We all need a car to get from A to B. Some have an old Ford Pinto engine (anybody remember the old Ford Pintos?!) while some have a high-performance Ferrari engine. It is easy to see the big difference in en

speed allows executive functions to be performed quickly, efficiently, and appropriately. Now, just because you don’t have a Ferrari engine doesn’t mean you cannot travel from point A to point B, but the efficiency of the journey depends heavily on your processing speed/engine. We all need a car to get from A to B. Some have an old Ford Pinto engine (anybody remember the old Ford Pintos?!) while some have a high-performance Ferrari engine. It is easy to see the big difference in en gine capability! That sums up processing speed in very simple terms. Just about any working car will get you from A to B, but the ride is clearly more pleasant (and faster!) in some models than in others. You may hit bumps in the road either way, but a high-performance engine allows for a faster, smoother, more pleasant ride with much less effort. That’s processing speed – in simple terms.

gine capability! That sums up processing speed in very simple terms. Just about any working car will get you from A to B, but the ride is clearly more pleasant (and faster!) in some models than in others. You may hit bumps in the road either way, but a high-performance engine allows for a faster, smoother, more pleasant ride with much less effort. That’s processing speed – in simple terms.

Now, that’s a useful metaphor, but after my conversation with Dr. McCloskey, I realized that it is not always this way. We could reverse this metaphor and say that processing speed is the car and executive function is the engine. It is possible to have a good car with engine trouble. Plus, some engines are built for speed while some are built for power. Maybe some are built for both. Maybe some cannot handle either speed or power.

Impact of Slow Processing Speed

Slow processing speed can manifest itself in many ways in a learner’s life. In fact, it can impact all areas of functioning. Take a look at the skills that can be negatively influenced by slow processing speed:

- Processing spoken information

- Processing written information

- Speaking

- Organizing thoughts

- Writing information on paper

- Typing information on a keyboard

- Reading fluently

- Understanding directions

- Retrieving information from long-term memory

- Finishing almost anything

- Social interactions

- Anything that is timed

- Focusing on a task

(Braaten & Willoughby, 2014)

Focusing on a task may seem like an attention problem, but it might not be. The cause could be that information comes in so quickly that attention is lost because the listener simply cannot keep up with the speed of input. Slow processors are often considered to be inattentive, when often, that is not the case at all.

When we consider all of the skills impacted by slow processing speed, we see that slow processing impacts all areas of a learner’s life, whether oral (listening, speaking, social interactions) or written (reading, writing). The struggle is real at school, at home, at play, on a sports team, at a piano lesson, at a birthday party, and so on.

Slow Processing Speed and Reading, Attention, Math

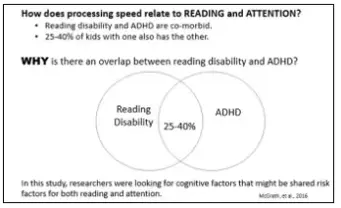

The connection between processing speed, reading, and attention (and as we will see – math) is clear. R eading disability and ADHD are co-morbid; 25-40% of kids with one have the other.

eading disability and ADHD are co-morbid; 25-40% of kids with one have the other.

Why is there an overlap between reading disability and ADHD? Is there any cognitive risk factor that will put a learner at risk for both ADHD and Reading Disability? The definitive answer is, yes!

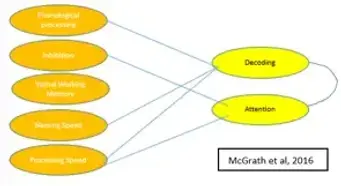

Look at the predictors of decoding success:

- Phonological processing

- Naming speed

- Processing speed

Now look at the predictors of attention:

- Inhibition

- Procession speed

Did you notice that the only factor shared by reading predictors and attention predictors is processing speed? That should tell us something.

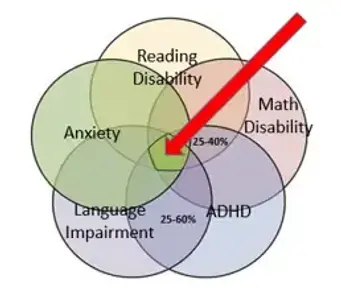

When we add math to the mix, we find that processing speed affects reading, attention, and math ability. Processing speed is the only common factor to all three issues (McGrath, et al., 2016). Therefore, processing speed is a generalized risk factor for many different academic outcomes. Its impact on reading is related to both fluency and decoding. Additionally, its association with attention may seem counter-intuitive because children with more attention problems are slower to perform processing speed tasks even though they may seem hyperactive. These same kiddos who seem to race through life actually work more slowly. When it comes to math, both fluency and computation seem to be affected.

Perhaps slow processing speed can help explain why we see high rates of comorbidity in children with learning and attention challenges. Look at the intersection of math disability, ADHD, language impairment, anxiety, and reading disability. Is that processing speed in middle? New research seems to indicate that it is indeed.

Consider that one third of students with slow processing speed have anxiety disorder. They worry about their performance, tests, and assignments, and they are often self-conscious, perfectionistic, and have social and pragmatic difficulties. It is easy to see how this all adds up to anxiety. Understand that slow processing speed does not cause anxiety, but it does impact it. Interestingly, people with mood issues, such as depression, anger, irritability, frustration, discouragement, and fatigue, tend to process information more slowly. A main symptom of depression is slower motion and slower motivation.

A Closer Look at Reading

Further research reveals more support for the connection between processing speed and reading.

Reading ability, including fluency, is linked to processing speed…Further, the effects of processing speed on reading fluency can subsequently affect further development of more complex academic skills such as reading comprehension (Wolf & Katzir-Cohen, 2001) highlighting the interdependence of automaticity and comprehension. In other words, as reading becomes more automatized, less mental effort and attentional resources are required for ongoing decoding and accurate word reading; thus, these resources can be allocated to the task of translating text into meaning. (Mahone, 2011)

Let’s look specifically at the connection between reading fluency and processing speed. We think of reading fluency as how fast you read – the rate. That’s part of it, but it’s only one part. Reading fluency includes appropriate rate, intonation, and phrasing, and it is difficult to construe true meaning and comprehend what you are reading without all three components (McGrath, et al., 2016). This is how processing speed impacts comprehension – in order to truly comprehend what you are reading, you must read at a good rate with good phrasing and with good intonation. All of this together allows you access meaning. This goes for oral reading as well as silent reading; even fluent silent reading requires intonation, phrasing, and speed (McGrath, 2016). Understand that silent reading does not fix a fluency problem.

Improving Processing Speed

While many “experts” are busy debating whether or not processing speed can be improved, NILD educational therapists are busy improving processing speed in learners! NILD, along with other great mediators like Professor Reuven Feuerstein, recommend teaching metacognition – thinking about your thinking. As the rest of the educational, medical, and psychological communities catch up, NILD therapists have known the value of teaching metacognition for decades. That’s why we do what we do, and that’s why what we do works.

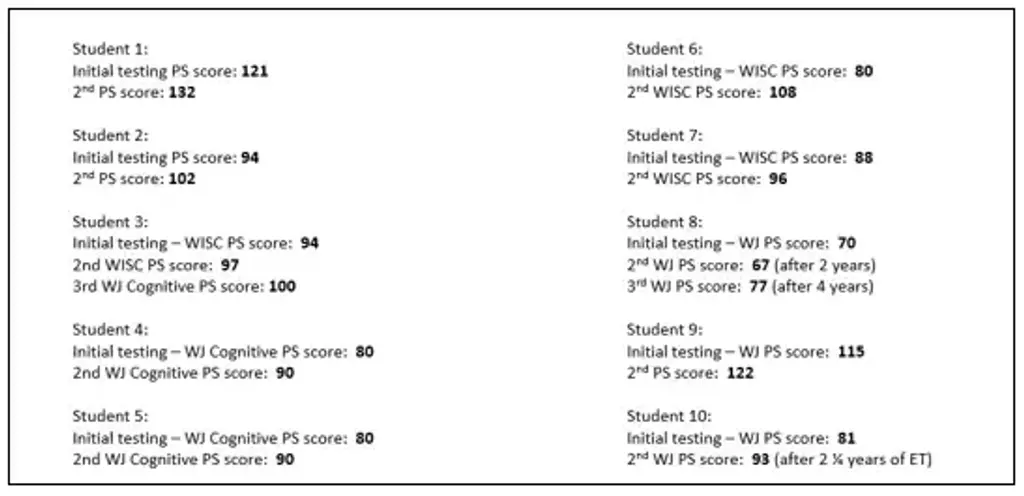

Take a look at these scores from NILD students who participated in one-on-one educational therapy. These scores come from NILD legends Bridget Hughes and Vesta Gillette. Look at those increases. Yes, you can improve processing speed!

I shared some of these scores with Dr. George McCloskey, who told me, “I agree with you that processing speed can be changed, and that remedial efforts can make a difference. There are many possibilities that could explain score increases; one is familiarity with a task…” He continued, “…Correction of executive function inefficiencies also would cause an increase in scores…My experience has been that if you consciously target a cognitive function for change, you will see some form of improvement, especially if strategies are provided to assist with improving efficiency (personal communication, June 10, 2016).

Several years ago, NILD’s Discovery Program leadership team spent a summer reading research on processing speed. They were on a quest to learn how to impact student’s processing speed that could be measured in a variety of areas. They wondered if processing speed could be harnessed – or unleashed. They wondered, as NILD educational therapists, can we get to the root of developing an efficient processing speed in learners.

After much study, the team concluded that NILD therapists do indeed have the tools (tried, tested, and proven over the years) to positively impact processing speed, and in particular one specific technique can work wonders. Can you guess which technique? If you guessed Rhythmic Writing, then you are right! Some of you may need to begin to think differently about Rhythmic Writing. Yes, it develops fluidity in grapho-motor skills, but it can also be used to impact processing speed because Rhythmic Writing targets a wide variety of executive functions. By tapping into a variety of executive function skills, it is improving processing speed. As Dr. McCloskey said, “Correction of executive function inefficiencies also would cause an increase in [processing speed] scores.”

Help For Slow Processors

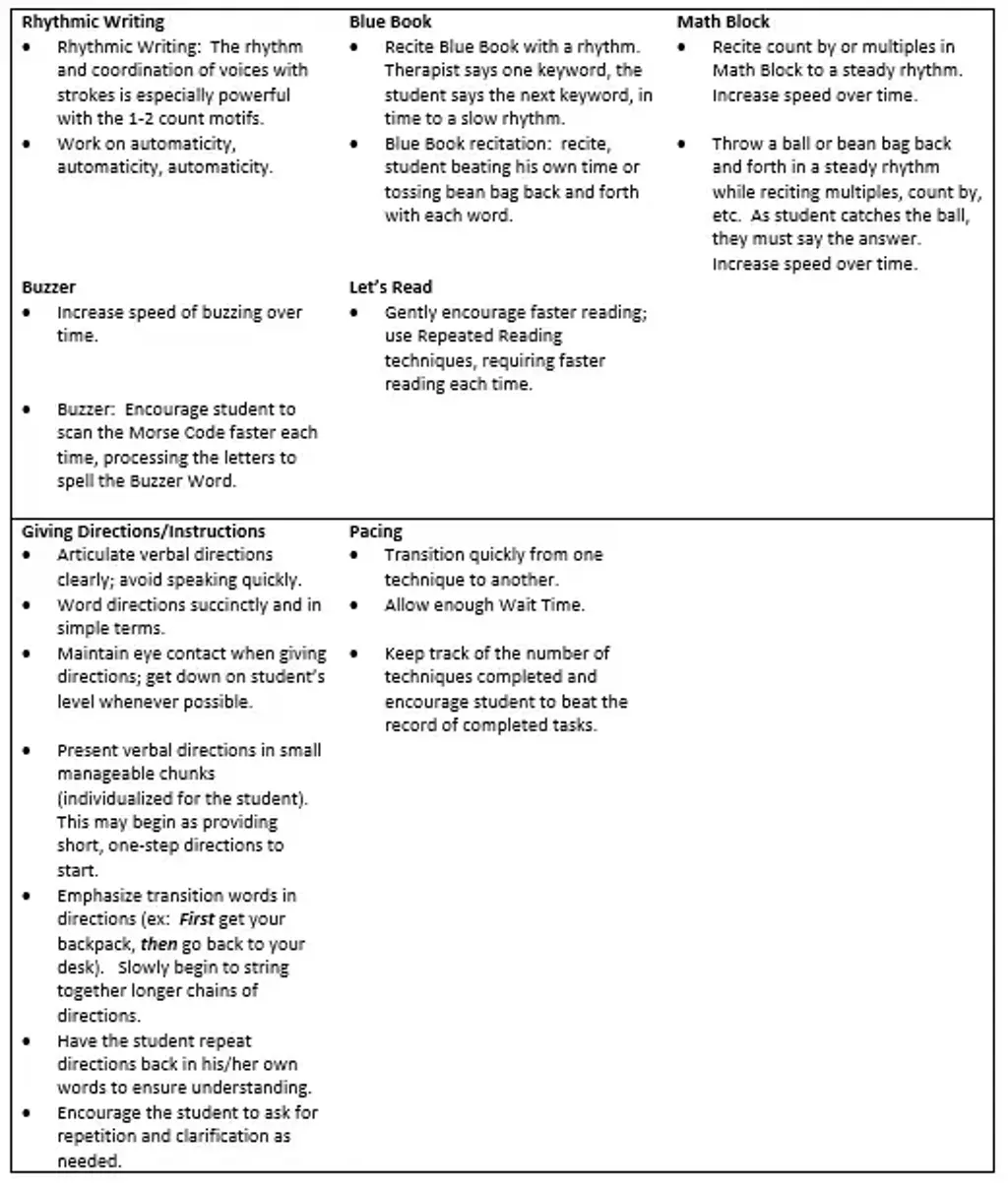

There is a lot that NILD therapists can do to positively impact processing speed. Rhythmic Writing, of course, is a powerhouse, and it plays an important role in therapy sessions. In an interview with Dr. Kathy Hopkins, pediatric neurologist, Dr. R. Lewis asserted, “Rhythmic Writing is one of the best techniques for training attention that I have ever seen.” Since attention is part of executive function, perhaps that’s why Rhythmic Writing makes such a powerful impact on processing speed. Here is an additional list educational therapists can do to help slow processors:

In Summary

- Processing speed affects social, emotional, and academic performance – all areas of life.

- Think Time is crucially important for slow processors. Train them to advocate for their own “think time.”

- When “you consciously target a cognitive function for change, you will see some form of improvement, especially if strategies are provided to assist with improving efficiency” (McCloskey).

- Processing speed affects reading, attention, and math abilities.

- Improving executive functions can improve processing speed. Many NILD techniques improve executive function, including Rhythmic Writing.

- NILD mediation does indeed positively influence processing speed.

Lorri Wilke, M.Ed., PCET, SL/DS

References

Braaten, E. & Willoughby, B. Bright Kids Who Can't Keep Up: Help Your Child Overcome Slow Processing Speed and Succeed in a Fast-paced World. (2014). New York: Guilford.

Feuerstein R., Falik L., Feuerstein, R.S., & Bohacs, K. (2013). A Think-aloud and Talk-aloud Approach to Building Language: Overcoming Disability, Delay, and Deficiency. New York: Teachers College.

Hopkins, K. (2004). “Rhythmic Writing Critique from the Perspective of Pediatric Neurology.”

Mahone, E. "The Effects of ADHD (Beyond Decoding Accuracy) on Reading Fluency and Comprehension." New Horizons for Learning Winter (2011): n. p. Johns Hopkins School of Education. Web. 30 May 2016.

McCloskey, G. & Perkins, L. (2013). Essentials of Executive Functions Assessment. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

McCloskey, G. "Processing Speed and Executive Functions." E-mail interview. 10 June 2016.

McGrath, L., Fagen, D., & Wood, M. "Lab School Lecture Series - Lauren McGrath, PhD." YouTube. YouTube, 02 Mar. 2016. Web. 1 May 2016.

Parks, W. (2011). “The Nuts and Bolts of Processing Speed.”

McGrath, E.G., Willcutt, L.M., Olson, R.K., Peterson, R.L., Boada, R., & Pennington, B.F. "Cognitive Prediction of Reading, Math, and Attention: Shared and Unique Influences." Journal of Learning Disabilities (2016): n. p. Web. 1 May 2016.