Thoughts on Initial Evaluations for NILD Educational Therapy

Educational Therapy Strategies

Written by: Kathy Keafer

August 19, 2019

I have always found that August and September were busy months when it comes to evaluating the learning needs of students in our schools. While many parents have had the foresight to consider intervention needs for their children who are struggling academically in the closing months of the previous year, some parents do postpone their search and decisions to just before school opens. Also, the logistics of ending one school year and beginning another usually means that we are heavily engaged in initial evaluations as a new year gets underway. One of the things I am most grateful for in education is the opportunity for new beginnings and considering the needs of those individuals who are not finding academic success could be just the fresh start that will make all the difference for them in the coming school year.

I have always found that August and September were busy months when it comes to evaluating the learning needs of students in our schools. While many parents have had the foresight to consider intervention needs for their children who are struggling academically in the closing months of the previous year, some parents do postpone their search and decisions to just before school opens. Also, the logistics of ending one school year and beginning another usually means that we are heavily engaged in initial evaluations as a new year gets underway. One of the things I am most grateful for in education is the opportunity for new beginnings and considering the needs of those individuals who are not finding academic success could be just the fresh start that will make all the difference for them in the coming school year.

We are all aware of the different models of evaluation and assessment that are used in order to identify the learning needs of students. For many years, an aptitude-achievement discrepancy model was exclusively used to identify those with learning differences. More recently, public educators, as a result of new language added in IDEA 2004, are able to use a response to intervention (RTI) model to determine those students in need of specialized intervention services and are no longer required to determine if an aptitude-achievement discrepancy does exist. In addition, in Learning Disabilities and Challenging Behaviors, Mather, Goldstein and Eklund (2015) describe an alternative method, also with provision for use within IDEA, for us to consider.

This alternative method, known as a Pattern of Strengths and Weaknesses Model (PSW) explores whether a child “exhibits a pattern of strengths and weaknesses in performance, achievement, or both, relative to age, state approved grade-level standards, or intellectual development” (Ihori & Olvera, 2015, p.3). When determining specific learning disability (SLD) a PSW approach features “multiple sources of data collected over a period of time using a variety of assessment tools and strategies” as well as the techniques that identify patterns within the data and related logical evidence that guides decision making about the need for intervention (Schultz, Simpson & Lynch, 2006, p. 87). Proponents of PSW contend that these methods of cognitive assessment can be used to plan treatment and to differentiate students with SLD from other students with more global deficits (Miciak, Fletcher, Stuebing, Vaughn, & Tolar, 2013) and will point to processing deficits that interfere with a student’s ability to perform academically as it establishes links between cognitive processing and academic achievement (Schultz et al., 2006).

When I began my career with NILD in 1987, we were certainly proponents of the importance of understanding the aptitude-achievement differential in the students identified as needing educational therapy. Over the years, we have continued to help educational therapists understand how this discrepancy can affect the academic achievement of our students because it does remain important to preparing appropriate intervention for the students we serve. When the RTI model was first introduced in the early 2000s, I was skeptical of its use and wondered if it might limit a deeper understanding of the needs of our students since a full educational evaluation was not required for identification of SLD. However, in returning to school administration, I have seen the power of providing early intervention in an RTI type model for students who are struggling with basic skills and then recognizing the need for a more complete evaluation as students reaching late second grade or third grade are not achieving in ways commensurate with their peers. At that point, we should want to know the underlying cognitive processes that are hindering academic achievement and a more thorough assessment can help us better understand the needs and plan appropriate intervention.

The assessment battery recommended by NILD provides much rich information to help us better determine the needs of our students and match appropriate techniques to deficits recognized within the group of evaluations. It begins with a cognitive assessment, usually the WISC V if the evaluation is being done by a public school or private practice psychologist. However, if you can access the Cognitive Battery of the WJ IV, you will get improved alignment with the scores on that test as related to the scores on the WJ IV Achievement battery that you give leading to more valid indicators of strengths and weaknesses.

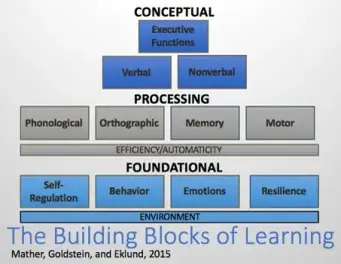

Know that it is important to have a person specifically trained and certified in providing cognitive assessments do this test as it adds a needed layer of ethical consideration of how the student is currently functioning. There is safety in having another professional speak into the assessment process. Typically, cognitive tests provide needed information to help us better understand the conceptual blocks as described in Learning Disabilities and Challenging Behaviors, our excellent course textbook. Additionally, you will glean information to help us understand challenges within the areas of memory and self-regulation. I would recommend that you often refer to the model of the components of learning related in this book as you work to understand better the students you serve.

Once a cognitive assessment is completed, we can begin to see if there is need to continue to pursue deeper evaluations via achievement tests as well as other formal and informal measures. You are all familiar with the recommended battery that we use in NILD but know that primarily what is learned from these measures is related to the processing blocks in the Mather, Goldstein and Eklund (2015) model. Additionally, we glean needed information regarding academic skills from the formal and informal evaluations we complete in NILD initial testing. Please be sure always to consider BOTH processing skills AND academic skills as you piece together the strengths and challenges of your students. Your initial testing report should provide quality information in both areas. Also, in your report should be observational information that comes from both the evaluator and the classroom teachers. From that information we can glean how the student is functioning not only academically but also in ways related to the possible needs in the foundational blocks.

As I consider this newer model of Patterns of Strengths and Weaknesses (PSW), I believe we at NILD are on a path towards this more dynamic form of assessment. It will be worth considering in the coming years if there are ways we can enhance our initial assessment to include additional data gathering methods that will even more effectively help us recognize the cognitive processes of our students that need to be addressed in our educational therapy sessions. According to Mather, Goldstein, and Eklund (2015), the “ultimate goal of a PSW approach is to document a student’s patterns of strengths and weaknesses so as to provide better services and more targeted interventions (p. 218). And as NILD Educational Therapists, that is our goal as well.

Dr. Kathy Keafer, Adjunct Professor: Liberty University

References

Ihori, D. & Olvera, P. (2015). Discrepancies, responses, and patterns: Selecting a method of assessment for specific learning disabilities. Contemporary School Psychology, 19 (1), 1-11.

Mather, N., Goldstein, S. & Eklund, K. (2015). Learning disabilities and challenging behaviors: Using the building blocks model guide intervention and classroom management. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks.

Miciak, J., Fletcher, J., Stuebing, K., Vaughn, S. & Tolar, T. (2014). Patterns of cognitive strength and weaknesses: Identification rates, agreement, and validity for learning disabilities identification. School Psychology Quarterly. 29 (1), 21-37.

chultz, E., Simpson, C. & Lynch S. (2006). Specific Learning Disability Identification: What constitutes a pattern of strengths and weaknesses? Learning Disabilities, 18 (2), 87-97.